Constant calls at all hours. Threats that sound terrifying but aren't legal. Collectors contacting your family, your boss, anyone who will listen. If this is happening to you, you're not alone — and you don't have to take it.

The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1692, is a federal law that protects you from abusive, deceptive, and unfair debt collection practices. It gives you real power to fight back against collectors who cross the line — and to recover money when they do.

This guide covers everything you need to know about the FDCPA in 2026: what it is, who it covers, what debt collectors can and cannot do, your rights, how to file complaints, and what damages you can recover. Whether you're dealing with harassing phone calls, threats, or a collector who simply won't stop, this page will help you understand your options.

In This Guide

- What Is the FDCPA (Fair Debt Collection Practices Act)?

- Who Does the FDCPA Cover?

- Prohibited Debt Collection Practices Under the FDCPA

- Prohibited vs. Allowed Debt Collector Behaviors

- Your Rights Under the FDCPA

- How to File an FDCPA Complaint

- Damages and Remedies Available Under the FDCPA

- Statute of Limitations for FDCPA Claims

- Regulation F: The 2021 FDCPA Update You Need to Know

- FDCPA vs. State Debt Collection Laws

- Frequently Asked Questions About the FDCPA

What Is the FDCPA (Fair Debt Collection Practices Act)?

The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act is a federal law enacted in 1977 and codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1692 et seq. It was designed to eliminate abusive, deceptive, and unfair debt collection practices while ensuring that ethical debt collectors can still operate within the law.

The FDCPA works by setting clear rules for how third-party debt collectors can communicate with consumers. It prohibits specific behaviors — such as threats, harassment, and dishonesty — and gives consumers the right to sue collectors who break these rules.

Two federal agencies share enforcement responsibility. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is the primary regulator, writing rules that interpret the FDCPA and taking enforcement actions against collectors who violate it. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) also has authority to pursue deceptive and unfair collection practices.

In 2021, the CFPB issued Regulation F (12 CFR Part 1006), the most significant update to federal debt collection regulation in decades. Regulation F modernized the FDCPA's communication rules to account for texts, emails, and social media — and established the first-ever call frequency cap of seven calls per debt within a seven-day period. More on Regulation F below.

Who Does the FDCPA Cover?

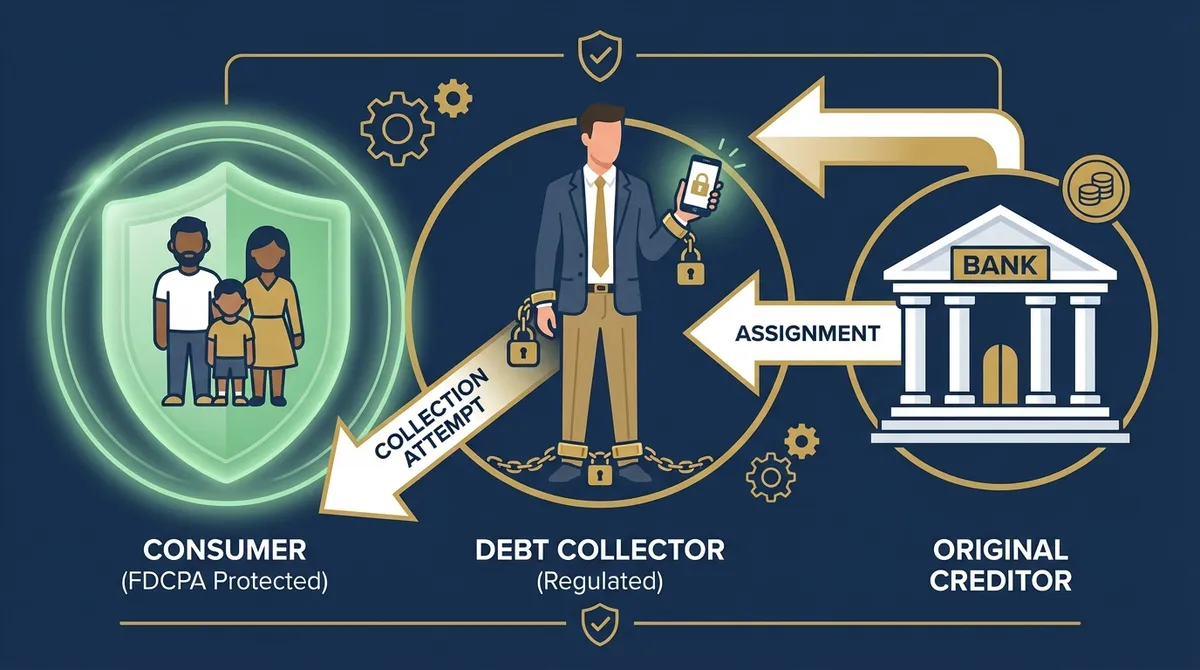

The FDCPA involves three parties, and understanding who falls into each category is essential to knowing whether the law protects you.

Consumers are any natural person who is obligated — or alleged to be obligated — to pay a debt. You don't have to actually owe the money to be protected. If a collector contacts you about a debt, the FDCPA applies to how they treat you regardless of whether the debt is valid.

Debt collectors are people or companies who regularly collect debts owed to someone else. This includes collection agencies, debt buyers who purchase delinquent accounts, and attorneys who regularly engage in debt collection activity. If a third party is trying to collect money from you, they are almost certainly covered by the FDCPA.

Creditors — the original companies you owed money to — are generally not covered by the FDCPA when collecting their own debts. However, there is an important exception: if a creditor uses a different name that would suggest a third party is involved, the FDCPA may still apply.

Types of Debts Covered

The FDCPA covers personal, family, and household debts. This includes credit card debt, medical bills, auto loans, mortgages, student loans, and personal loans. If the debt was incurred for personal or family purposes, it falls under the FDCPA's protections.

Business and commercial debts are not covered. If a collector is pursuing a debt you incurred for business purposes, the FDCPA does not apply — though state laws may still offer protections.

Who Is NOT Covered by the FDCPA

Not every entity that tries to collect a debt qualifies as a "debt collector" under the law. Original creditors collecting their own debts using their own name are excluded. In-house collection departments generally fall outside the FDCPA — unless they use a name that suggests a separate third party is doing the collecting. Certain government entities collecting specific types of debts are also excluded.

Prohibited Debt Collection Practices Under the FDCPA

This is the core of the FDCPA. The law organizes prohibited conduct into three categories, each addressing a different type of abuse. For a deeper look at how these behaviors affect consumers, read our guide on understanding debt collection harassment.

Harassment or Abuse (§ 1692d)

Debt collectors cannot use conduct designed to harass, oppress, or abuse you. Specifically, they are prohibited from:

- Threatening violence or harm against you, your reputation, or your property

- Using obscene or profane language during collection calls

- Calling repeatedly with the intent to annoy, abuse, or harass you

- Publishing your name on a "shame list" of people who allegedly refuse to pay debts

- Calling you without identifying themselves as debt collectors

False or Misleading Representations (§ 1692e)

Collectors cannot lie to you or mislead you to collect a debt. The FDCPA prohibits:

- Falsely claiming to be attorneys, government officials, or law enforcement

- Misrepresenting the amount you owe

- Threatening legal actions they cannot or do not intend to take — such as threatening arrest or wage garnishment without a court order

- Implying that non-payment of a debt is a crime

- Communicating false credit information, including failing to report a disputed debt as disputed

Unfair Practices (§ 1692f)

The FDCPA also bans debt collection methods that are simply unfair, even if they don't fall neatly into harassment or deception. Collectors cannot:

- Collect fees, interest, or charges not authorized by the original agreement or by law

- Deposit a post-dated check before the date written on it

- Threaten to seize or repossess property they have no legal right to take

- Contact you by postcard, which could expose your debt to anyone who sees your mail

Debt Validation Requirements (§ 1692g)

Within five days of first contacting you, a collector must send a written validation notice that includes the amount of the debt, the name of the creditor, and a statement of your right to dispute the debt within 30 days. If you dispute the debt in writing within that window, the collector must stop all collection activity until they provide verification.

Prohibited vs. Allowed Debt Collector Behaviors

One of the most common questions consumers have is where the line falls between legal and illegal collection activity. The table below puts the most common scenarios side by side.

| Prohibited (Illegal) | Allowed (Legal) |

|---|---|

| Calling before 8 a.m. or after 9 p.m. in your time zone | Calling between 8 a.m. and 9 p.m. |

| Calling your workplace after being told to stop | Sending letters or emails with a clear opt-out option |

| Threatening you with arrest or jail | Contacting your attorney if you have one |

| Using abusive, obscene, or threatening language | Reporting accurate debt information to credit bureaus |

| Calling more than 7 times in 7 days per debt (Regulation F) | Filing a legitimate lawsuit for a valid, non-time-barred debt |

| Discussing your debt with third parties (neighbors, coworkers, friends) | Leaving voicemails that comply with limited-content message requirements |

| Misrepresenting the amount owed or who they are | Contacting you to verify your address or employment (limited disclosure) |

Keep in mind that this table reflects federal law. State laws — such as Florida's Florida Consumer Collection Practices Act (FCCPA) — may provide additional protections beyond what the FDCPA requires.

Your Rights Under the FDCPA

The FDCPA doesn't just prohibit bad behavior — it gives you specific tools to take control. Here are the rights you can exercise today.

1. Right to request debt validation. Within 30 days of a collector's initial contact, you can send a written request demanding they prove the debt is yours and that the amount is correct. The collector must stop all collection activity until they respond with verification.

2. Right to send a cease-and-desist letter. You can tell a collector in writing to stop contacting you entirely. Once they receive the letter, they can only contact you to confirm they are stopping collection efforts or to notify you of a specific legal action. For step-by-step instructions, see our guide on how to stop debt collection harassment.

3. Right to restrict contact methods and times. You can tell collectors not to call you at work, not to contact you at certain times, or to communicate only in writing. They must honor these requests.

4. Right to dispute the debt. If you believe the debt is inaccurate or not yours, you have the right to dispute it. The collector must then verify the debt before continuing any collection activity.

5. Right to sue the collector. If a collector violates the FDCPA, you have the right to file a lawsuit in state or federal court within one year. You may recover actual damages, statutory damages, and attorney's fees.

6. Right to be free from workplace contact. If you or your employer tells a collector that you cannot receive collection calls at work, they must stop contacting you there.

An important note: exercising these rights does not eliminate the underlying debt. You may still owe the money. But these rights control how collectors are allowed to communicate with you — and they give you legal recourse when collectors break the rules.

How to File an FDCPA Complaint

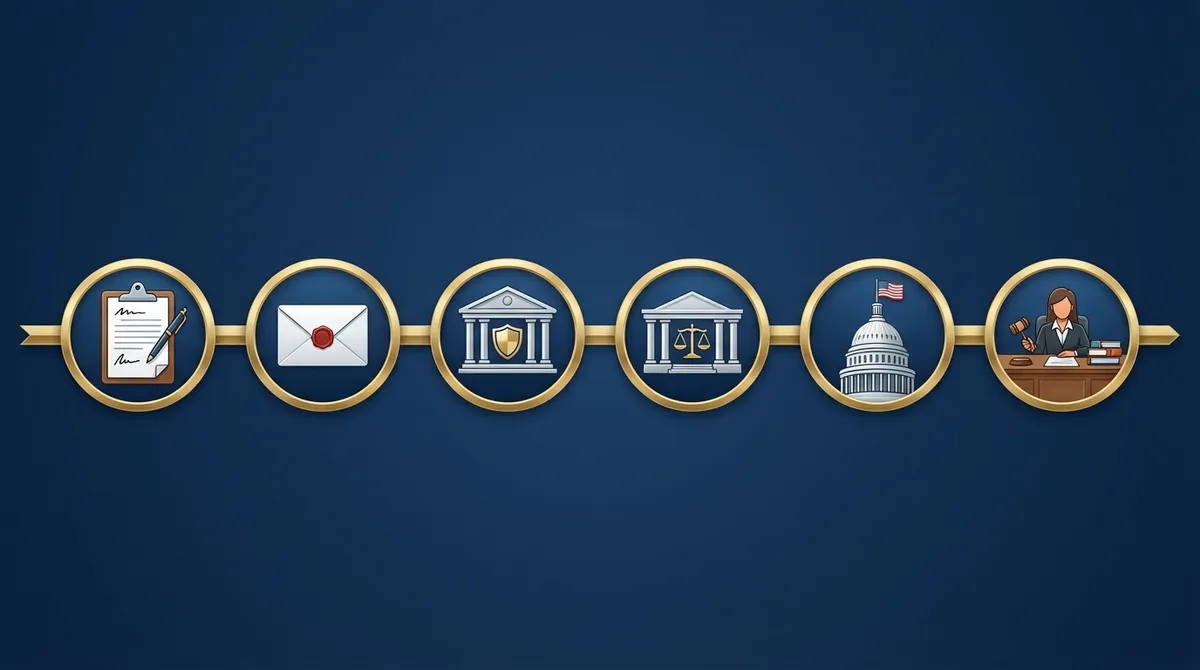

If a debt collector has violated your rights, taking action quickly strengthens your position. Here's a step-by-step process.

Step 1: Document everything. Save call logs, voicemails, letters, text messages, and emails. Write down dates, times, and what was said. This evidence is the foundation of any complaint or lawsuit. For detailed guidance, see our article on FDCPA record keeping and evidence.

Step 2: Send a written cease-and-desist or debt validation letter. Mail it via certified mail with return receipt requested so you have proof the collector received it.

Step 3: File a complaint with the CFPB. Go to consumerfinance.gov/complaint to submit your complaint. The CFPB forwards it to the collector and tracks their response.

Step 4: File a complaint with the FTC. Report the violation at reportfraud.ftc.gov. The FTC uses complaint data to identify widespread patterns of abuse.

Step 5: Contact your state attorney general's office. Many states have their own consumer protection divisions that investigate debt collection violations.

Step 6: Consult an FDCPA attorney. A qualified lawyer can evaluate whether you have grounds for a lawsuit — and most FDCPA attorneys work on contingency, meaning you pay nothing upfront. Learn more about handling debt collection harassment complaints and how to choose the right FDCPA attorney.

Filing complaints isn't just about your case. The paper trail you create helps regulators identify patterns of abuse and hold repeat offenders accountable.

Damages and Remedies Available Under the FDCPA

When a debt collector violates the FDCPA, you can recover money. The law, under 15 U.S.C. § 1692k, provides three categories of damages.

Actual Damages compensate you for the real harm caused by the violation. This includes financial losses like lost wages or bank fees, as well as emotional distress — anxiety, sleep loss, depression, and the toll that relentless harassment takes on your daily life.

Statutory Damages of up to $1,000 per lawsuit are available regardless of whether you suffered provable financial harm. You don't have to show a single dollar of actual loss to recover this amount. In class action cases, statutory damages can reach up to $500,000 or 1% of the collector's net worth, whichever is less.

Attorney's Fees and Court Costs are paid by the collector if you win. This is what makes FDCPA cases viable for consumers — because the collector pays your legal fees, most FDCPA attorneys take these cases on contingency at no upfront cost to you. To understand how this works in practice, read about how an FDCPA attorney can help you.

These damages are per lawsuit, not per violation. However, multiple violations within the same case strengthen your position and can influence the amount courts award. Courts consider the frequency, persistence, and nature of the violations when determining damages.

Statute of Limitations for FDCPA Claims

You must file an FDCPA lawsuit within one year from the date of the violation (15 U.S.C. § 1692k(d)). Miss this deadline, and you may lose the right to sue — even if the violations were clear and well-documented.

This is an area where consumers often get confused, because the FDCPA statute of limitations is different from the statute of limitations on the underlying debt. The time limit on the debt itself — how long a creditor or collector can sue you — varies by state and debt type, and can range from three to ten years or more. The one-year FDCPA clock is about your right to sue the collector for breaking the law.

In some federal circuits, the "discovery rule" may apply. This means the one-year clock may start not on the date of the violation, but on the date you knew or should have known about it. However, not all courts apply this rule, so you should not rely on it.

The bottom line: if a debt collector has violated your rights, consult an attorney as soon as possible. Delay can cost you your case.

Regulation F: The 2021 FDCPA Update You Need to Know

On November 30, 2021, the CFPB's Regulation F (12 CFR Part 1006) took effect — the most significant update to federal debt collection regulation since the FDCPA was enacted. Here are the key changes that still shape debt collection practices in 2026.

Call frequency cap. For the first time, federal rules established a presumption of harassment based on call volume. A collector is presumed to be harassing you if they call more than seven times within seven consecutive days regarding a specific debt, or if they call within seven days after having a phone conversation with you about that debt.

Modern communication channels. Regulation F acknowledged that debt collection has moved beyond phone calls and letters. Collectors may now use email, text messages, and social media direct messages to contact consumers — but each electronic message must include a clear and conspicuous opt-out mechanism that you can use to stop further communications through that channel.

Limited-content messages. Collectors can leave voicemails designed to avoid disclosing your debt to third parties who might hear the message. These "limited-content messages" must follow specific language requirements and cannot include details about the debt itself.

Time-barred debt disclosures. When attempting to collect on a debt that is past the statute of limitations, collectors must now disclose that they cannot sue you to collect the debt. This prevents a common tactic where collectors tried to pressure consumers into paying time-barred debts by implying legal action was possible.

FDCPA vs. State Debt Collection Laws

The FDCPA sets a federal floor of protection, but many states have enacted their own debt collection laws that provide additional rights beyond what federal law requires.

Florida's Florida Consumer Collection Practices Act (FCCPA) is a strong example. Unlike the FDCPA, the FCCPA covers original creditors collecting their own debts — closing a significant gap in federal protection. The FCCPA also provides its own set of prohibited practices and allows consumers to recover actual and statutory damages.

This means that if a collector violates both the FDCPA and your state's consumer protection law, you may have claims under both. Filing claims under multiple statutes can strengthen your case and increase your potential recovery.

Because state laws vary significantly, it's important to consult an attorney who understands both the federal FDCPA and the consumer protection laws in your state. Hyslip Legal handles cases nationwide and can evaluate which federal and state claims apply to your situation. Learn more about our consumer protection services.

Frequently Asked Questions About the FDCPA

What is considered harassment by a debt collector?

Under the FDCPA, harassment includes repeated calls intended to annoy or abuse, threats of violence, use of obscene language, and publishing your name on a list of debtors. Regulation F adds a presumption of harassment when a collector calls more than seven times in seven days per debt. Any conduct designed to oppress or intimidate you may qualify.

How many times can a debt collector call you?

Under Regulation F, a collector is presumed to be harassing you if they call more than seven times within a seven-day period about a specific debt, or if they call within seven days after a phone conversation with you. State laws may impose stricter limits. Multiple debts may mean multiple call limits, as the cap applies per debt, not per consumer.

Can you sue a debt collector for harassment?

Yes. The FDCPA gives you the right to sue a debt collector who violates the law. You can recover up to $1,000 in statutory damages, actual damages for financial harm and emotional distress, and attorney's fees — which the collector pays if you win. Most FDCPA attorneys handle these cases on contingency at no cost to you.

What happens when you report a debt collector for harassment?

Filing a complaint with the CFPB or FTC creates an official record of the violation. The CFPB forwards your complaint to the collector and requires a response. Regulators use complaint data to identify repeat offenders and bring enforcement actions. Your complaint also strengthens any future legal claims.

Can a debt collector contact my family or employer?

A debt collector can contact third parties only to obtain your contact information — and even then, they generally cannot reveal that you owe a debt. They cannot discuss your debt with your family, friends, neighbors, or coworkers. If you tell a collector not to contact you at work, they must stop. Violations of these rules are grounds for an FDCPA claim.

Do I still owe the debt if a collector violates the FDCPA?

Yes. An FDCPA violation by a collector does not eliminate the underlying debt. However, it does give you the right to sue the collector for damages. In some cases, your attorney may be able to use an FDCPA claim as leverage in negotiations over the debt itself.

How much can I get for an FDCPA violation?

You can recover up to $1,000 in statutory damages per lawsuit, plus actual damages (financial losses and emotional distress), plus attorney's fees. The total recovery depends on the severity and frequency of the violations. In class actions, statutory damages can reach $500,000 or 1% of the collector's net worth.

Does the FDCPA apply to original creditors?

Generally, no. The FDCPA applies to third-party debt collectors, not to original creditors collecting their own debts. However, if a creditor uses a different name that suggests a third party is collecting, the FDCPA may apply. Additionally, many state laws — such as Florida's FCCPA — do cover original creditors. For frequently asked questions about consumer protection beyond the FDCPA, visit our FAQ page.

This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reading this page does not create an attorney-client relationship with Hyslip Legal, LLC. Every situation is unique, and individual results may vary — past outcomes do not guarantee future results. Contact Hyslip Legal for a free consultation to discuss your specific circumstances.

Last Updated: February 2026